GCP – Silos are for food, not data — tackling food waste with technology

While 40% of food in America goes to waste, 35 million Americans (likely even more during this pandemic) are food-insecure—meaning they are without food or not sure where future meals will come from. In addition, food waste has been called the “world’s dumbest environmental problem.” As the pandemic continues, the food system is in the spotlight. Farmers are plowing their crops back into their fields, restaurants are struggling to get back into business, and millions of newly unemployed Americans are lining up at food pantries. Leaders in the industry are looking to move more food to the right place as governments and philanthropists look to deploy capital to improve the situation. Moving things and moving money require, first and foremost, good data and a common language for describing food in the supply chain.

As an early-stage team from X, an Alphabet subsidiary, worked on this moonshot, they worked closely with Kroger and Feeding America®️ to explore, transform and analyze datasets using Google Cloud technology.

While our food sits securely in silos and storehouses across the U.S., information about the quality and quantity of that food also sits static in silos, with the latter benefitting no one. By sharing raw data with X as the neutral information steward, Kroger and Feeding America have discovered potential systems-level opportunities for change, beyond optimizing their own organizations.

In a world where data is a highly valued corporate asset, sharing data may be viewed as a strategic and competitive risk, not to mention the legal, operational and technical hurdles. But it can lead to huge benefits, too. We’re sharing our collective story because we’ve learned a lot about how three very different organizations can work together to achieve industry-wide goals while ensuring that each organization’s data assets are secure. We found that solving industry-wide challenges starts with sharing datasets. Here’s how un-siloing data led to advances in reducing food waste.

What are data silos and why do they exist?

Data siloing is an information management pattern where relevant and interrelated subsystems are unable to communicate with one another in real-time, due to logical, physical, technical, or cultural barriers to their interaction. For example, a human resources system may be isolated from other company systems to protect sensitive employee information, but when compensation information is updated in the finance department, information across the two systems needs to be reconciled manually.

Data silos are pervasive across industries and organizations. In government and policy circles, experts talk about “stovepiping,” application architects talk about “disparate systems,” and organizational culture consultants talk about incompatible “subcultures.” In each case, the end results are similar: Even with vast amounts of data, decision makers struggle to access data, process it, find the answers they need, and respond quickly. When X, Feeding America and Kroger came together, they first had to address underlying organizational obstacles.

-

Mandates and beliefs: Each party had a different vision for coming together—some were focused on sustainability, and others on food security—and thereby had different data needs. At times, the data silos in place also reinforced inconsistent beliefs. For example, certain food banks were concerned that retail donations were dwindling, while Kroger had plenty to donate, but had not yet operationalized that data.

-

Organizational fears: It took courage for Feeding America and Kroger to share what was behind the curtain, exposing their own challenges with data quality and standards. The individuals who led this project also had to face corporate approval processes and articulate why each organization had more to gain by sharing than holding onto data as a form of power, and why they shouldn’t fear unlikely unintended consequences.

-

Technical limitations: While the leaders who came together had influence and decision-making power, they were not the technical staff who had the authority and knowledge to access the data and implement data pipelines. In addition, neither Kroger nor Feeding America was in a position to store and analyze each other’s proprietary data.

How to break through data silos

This three-way partnership was able to break through data silos by being strategic about how to build confidence and credibility with their respective organizations. Here are steps that the partnership took.

1. Align on objectives, then bring in others. The partners came together and fully clarified respective high-level goals, data assets needed to achieve these goals, and overall operating principles, before bringing in their respective legal teams to draft data-sharing agreements and move through executive approval processes. By doing so, champions for this project inside of each organization were able to negotiate internally with a clear rationale rather than following the traditional company policies.

2. Think big, start small. While the partners all believed in what was possible with a combined global source of truth and reinforced this vision to their superiors, each individual leader also made it easy for their respective corporations to sponsor this effort by starting small. Rather than going immediately to scale, this team prototyped with one store and one food bank and went deep, building everything end to end. Learnings were incorporated before asking the next ten stores and ten food banks to participate.

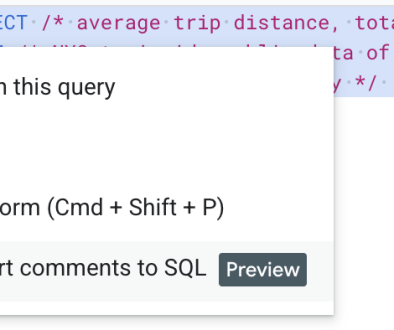

3. Make it frictionless to share. The X team invested in working with Kroger and Feeding America’s data teams to set up automated processes to schedule and sequence the transfer of data to Google Cloud regularly. This detailed case study explains how to set up extract, transform, load (ELT) processes using Cloud Composer.

4. Find a common language. Once the X Team had both Kroger and Feeding America datasets in BigQuery, Google Cloud’s enterprise data warehouse, they discovered that both organizations and their respective departments did not have a consistent language for locations, food items, quantities and other variables. There were at least 27 ways of representing Texas! The first step was to format the data to be consistent. As an example, this case study describes standardizing geolocation data using Maps API.

5. Show insights, early and often. The partnership was able to show, with initial analyses on one store or five food banks, immediate impactful opportunities. Examples include ways to do bulk sourcing of food between specific food banks for better pricing, and which days pantries should schedule their store pickups to get the most donated food. This earned the team additional support from sponsors and operational staff to continue scaling the broad data un-siloing effort. Check out further examples and tools.

Organizing the world’s food information

The X team working on this project has now joined the Google Food team to continue to grow their partnership with Kroger and Feeding America together on Google Cloud. This collaborative effort to solve for waste and hunger will continue with the confidence they need in the reliability and security of Google’s infrastructure at global scale.

Learn more about the technical details of this food waste project.

If you’d like to learn more and donate to these efforts, check out:

The X and Google team would like to thank Kroger, Feeding America, its member food banks, and St. Mary’s Food Bank for their contributions to this article.

Read More for the details.